A Moroccan Travelogue - Refined Beauty: Exploring the Soul of Craftsmanship in the Colors and Spaces of Fez

By: actCoupons | October 10, 2025

Fez has long been a city with the most developed handicraft industry in the Arab world, known as the "Athens of Africa," a tradition that continues to this day. In Fez, you can witness some of the most authentic handicrafts in Morocco and across North Africa and the Middle East, as well as the artisans who have inherited millennia-old techniques. Consequently, many visitors to Fez say: "Fez is a living, breathing copy of 'One Thousand and One Nights,' a dazzling Arabian Nights." Since the mid-12th century, this spirit of craftsmanship, rooted in tradition, natural inheritance, process guidance, and hands-on practice, has been a constant in the ancient vein of Fez. A favorite saying of Fez artisans is: "If you can do it by hand, never rely on machines!" It is thanks to generations of Fez artisans, with their exquisite skills and unshakable dedication, that we can truly and fully experience the wisdom and art of the Arabian Nights, as embodied in the legends of the Thousand and One Nights.

Fez's streets and alleys resemble a spiderweb, its houses aging and decaying, a glimpse back in time. Traditional handicraft shops line its narrow streets, offering a dazzling array of crafts. However, what captivated me most was not these, but the artisans who create these exquisite works, which piqued my curiosity and inspired me to learn more about them.

Fez is made up of thousands of narrow alleys. Without a local guide, first-time visitors can quickly become lost in the maze of Arabian Nights.

Almost every one of these narrow streets is lined with a variety of shops. Besides restaurants, butchers, and grocers, most sell handicrafts, including copperware, silverware, lamps, pottery, and carpets. All are handmade using ancient methods. The clanking sounds of hammering and the silent demeanor of the artisans create a unique landscape in Fez.

In a copper workshop less than ten square meters, an old craftsman is carving an exquisite copper plate. His eyes are almost fixed on the metal surface, and his small hammer strikes the carving knife with astonishing precision. Each blow is precisely placed, leaving a permanent mark without piercing the thin copper sheet. He doesn't need a blueprint; all the designs are in his mind. He tells the guide that he began learning this craft at the age of twelve and has been practicing it for over fifty years. "My father and grandfather both made this," he said, his fingers gently tracing the patterns on the copper. "I didn't invent these designs myself; they're from a long time ago."

This wasn't a show for tourists, but rather a backdrop to everyday life in Fez. What captivated me most were the workshops hidden deep in the streets, where artisans practiced ancient crafts.

As I continued to wander through the maze, I began to notice details often overlooked by tourists: the intricate geometric patterns carved into a wooden door, the metal of a doorknob polished to a shine by countless hands, the astonishing intricacy of exquisite copper pieces.

Such scenes can be found everywhere in Fez. In textile workshops, workers operate massive wooden looms, weaving intricate patterns. In leather workshops, artisans use traditional tools to cut and sew, creating exquisite shoes and bags.

In pottery workshops, artists hand-paint blue geometric patterns with delicate brushes, each piece a unique creation. They don't have modern machinery or computer-designed templates; they only have skills passed down through generations and a deep understanding of their materials.

Each street is like a hidden gem, with each turn revealing a new scene. Guides typically lead visitors through alleyways steeped in medieval Arabian charm, filled with handicrafts. An indescribable, mingled aroma of spices lingers in the air, accompanied by the relentless clatter of artisans hammering at copper and iron, immersing you in the vibrant atmosphere of the marketplace.

This is the most prestigious craft shop in the ancient city of Fez. Owner Mohammed El-Jenani is a renowned figure in Fez. El-Jenani's crafts have been commissioned and collected by numerous international dignitaries, celebrities, and Arab royalty. Photos of El-Jenani posing with the likes of Margaret Thatcher, President Clinton, Camilla, and King Morocco adorn the shop's walls.

The owner's confident expression clearly demonstrates the shop's exceptional quality. Shopaholics, hurry up and buy! In an age obsessed with efficiency and mass production, Fez artisans still adhere to time-consuming and laborious traditional methods, not out of nostalgia or conservatism, but because they deeply understand that these methods produce a quality and beauty that cannot be replicated by machines.

Their craftsmanship is reflected not only in their mastery of their skills but also in their respect for the process—they are willing to invest a disproportionate amount of time and effort in a single piece, believing that true value lies in this time spent.

Gazing upon these handicrafts before me, I was instantly captivated by their ultimate tranquility and intricacy. It was as if I had gained a more tangible sense of the city's artisanal soul.

Our group members eagerly began asking for prices, haggling, and bargaining, while the shopkeepers patiently explained and recommended items. Motor vehicles are prohibited in the old city (the narrow streets are practically impossible to navigate), so donkeys have become the primary means of transportation. As we emerged from the dark alleys and into the open air, we arrived at the famous honeycomb handmade dyeing workshops on the banks of the Fez River.

The thousand-year-old capital of Fez is a world-renowned city, often considered the setting for "The Arabian Nights." It's permeated with medieval Arabian charm, yet the air is permeated with an indescribable, strange smell—a stench! Why is such a beautiful city so "infamous"?

The story begins with Fez's renowned leather industry. Fez is one of the few places in the world that still maintains traditional leather making and dyeing practices. Fez's leather products are of top quality and are globally renowned. Luxury brands like Chanel and Louis Vuitton source their leather goods from here. Every day, donkeys carry the skins of cattle, sheep, and camels to the dyeing workshops on the edge of the old city.

Chaouwara Tanneries, a massive leather dyeing workshop near Place as-Seffarine in the old city, dates back to the 18th century. Their natural leather processing methods are said to have been preserved for over a thousand years. Hundreds of honeycomb-like stone vats are neatly arranged between bright yellow buildings, and workers with clearly defined roles bustle about at their respective stations.

Rooftops and walls are covered with skins hanging out to dry. Foul-smelling effluent from the leather industry pours continuously into the Fez River, transforming it into a filthy city sewer.

Not only do the workers toil in the open-air workshops under the scorching sun, but they also endure the pungent odor and the acidic and alkaline corrosion caused by feces and limewater. The conditions are harsh and extremely challenging. Yet, the traditional, handcrafted, natural leather processing methods they employ have been passed down for millennia and will continue to be used today and in the future.

It is said that when Arabs crossed the sea to Africa, they were amazed by the ancient Egyptians' miraculous embalming techniques. Ingenious leathermakers then incorporated some of these techniques into leather tanning. This leather, tanned from natural materials, is tough, durable, non-toxic, and suitable for next-to-skin use. It is therefore highly sought after by the upper classes and European royalty, making Fez leather renowned and renowned internationally!

Pinching a few fresh mint leaves handed out by the shopkeeper to your nostrils, you endure the stench and ascend to the three-story wooden building next to the dyeing workshop. You'll see hundreds of stone vats filled with red, green, and yellow dye neatly arranged in a vast courtyard, like a densely packed beehive.

Over 200 stone vats filled with red, green, and yellow dyes are spread across a courtyard covering over a thousand square meters, like a painter's palette. These dyes are all derived from the flowers, leaves, or fruits of natural plants, such as poppies for red, saffron or mustard for yellow, mint leaves for green, and mimosa powder for brown.

When leather is delivered to the leather dyeing workshop, workers first clean the hides with knives, then heat and disinfect the animal fur before soaking them in a pool of lime mixed with pigeon droppings, fish oil, and cow urine.

The dyed sheepskins are hung on the wall to air-dry. Finally, the dyed and air-dried leather is polished and refined. While these processes are old-fashioned and inefficient, they maximize the naturalness of the leather, making this hand-tanned leather a preferred choice for luxury brands like Chanel, Hermès, and Louis Vuitton. The old town of Fez was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1981, thanks in large part to the traditional leather dyeing workshops called Chaouwara Tanneries. The ancient dyeing workshops and the workers' meticulously crafted, historically accurate processes are among the most captivating sights of Fez and even the entire Morocco. It's no wonder many travel guides list them as must-sees in both Morocco and Fez.

Workers stand on the edge of the vibrantly colored dye vats, some inside or walking among them. Some dye leather, others wield knives to trim fur, some add water and other ingredients to the vats, and some carry plastic buckets filled with dye (manure) and tread briskly along the 10-centimeter-wide stone vats...

For a daily income of $30, these workers not only toil under the scorching sun, but also endure the pungent odor and the acidic and alkaline corrosion caused by manure and limewater, which puts them at high risk of developing skin diseases. Mixing this animal manure with limewater and then steaming it at temperatures reaching 40°C creates a primitive chemical reaction. The lime separates the fur, while the pigeon droppings soften the leather. After soaking for three to five weeks, the fat and protein in the fur completely dissolve. Workers, wearing leather jumpsuits (in the past, they went barefoot), then plunge into the stone vat of pigeon droppings and tread on them for over three hours to separate the fur and soften the hides. The stench drifts away with the wind, accompanied by the splashing waves.

The entire dyeing workshop maintains centuries-old traditional handcraftsmanship. Every process is manual, including the use of dye and manure, which workers scoop out from the stone vats and carry bucket by bucket to be emptied and replaced. After years of training, many workers resemble the skilled monks in the film "Shaolin Temple." Carrying plastic buckets filled with dye (fecal juice) in both hands, they swiftly walk along the edges of ten-centimeter-wide stone vats, maintaining remarkable balance while filling each vat accurately and efficiently.

The softened leather is then pulled out of the vats and washed with water. After a brief drying period, it moves on to the next step: dyeing with various natural plant dyes and softening again.

Leather tanning and processing are prominently listed among the three carcinogens published by the World Health Organization's International Agency for Research on Cancer. While traditional vegetable tanning is a natural process, bacteria and microorganisms in animal feces can still transmit malaria through wounds. Despite this, the stinking workers continue to happily scurry back and forth between the honeycomb-shaped dye vats, toiling away, a tormenting sight for all who observe.

The dyed hides are hung on the walls or spread on the rooftops to air-dry. Finally, the dyed and air-dried leather is polished and finely processed. While these processes are outdated and inefficient, they maximize the naturalness of the leather. You've probably heard stories of the Red Army boiling leather belts for food while climbing snow-capped mountains and crossing grasslands during the Long March! At that time, Chinese leather production used the vegetable tanning method, a similar process, except that the Chinese cured the hides with salt and then added lime or alkaline substances to de-lime and soften them.

The dyed and processed leather is cut into standard hides and sold worldwide. Any scraps are then transformed by local vendors into a variety of colorful Moroccan slippers, babouches, gloves, small leather goods, and soft bags. These vibrant leather products, imbued with a distinct Moroccan flair, are naturally popular with tourists, who enjoy the opportunity to purchase their desired leather goods while admiring the sights, creating a lively atmosphere among the visitors.

The furs, soaked in manure, are incredibly heavy, especially the massive camel hides, which can weigh hundreds of pounds. Even a strong man would struggle to lift them from the stone vats. Workers repeat this daily routine of trampling, dragging, washing, and hanging them up, with no time to wipe even their arms and faces smeared with manure.

A neatly dressed young man, despite being stained with manure, bent down to help a white-bearded elderly worker sitting by the dye vat, adjusting his leather jumpsuit. They resembled a father and son, the son seemingly visiting. Seeing his father, exhausted, resting at the edge of the vat, he leaped up to the vat and fixed the buckles. The scene was heartwarming and touching!

Most of Morocco's leather industry has become industrialized, but only in Fez does it still maintain traditional artisanal workshops. Many visitors to Fez praise the workers' exceptional craftsmanship. Whether working in bronze, pottery, textiles, or the infamous leather dyeing, they toil silently and diligently, unconcerned about whether their creations are commensurate with their rewards, determined to pass on their ancestral skills. This, perhaps, is the fundamental reason the dyeing workshops have survived for millennia.

The dyers at Fez dyeing workshops learn their craft from a young age, their knowledge coming not from books but from hands-on practice and accumulated experience. Standing at the edge of the dyeing workshops, I suddenly understood the true depth of time—this isn't the "history" protected by glass in a museum, but a living, breathing tradition.

The stench of the dyeing workshops permeated the air, now transforming into a pervasive yet intimate, living aroma. It led me through ever-narrower alleys, their walls rounded by time.

If I want to witness this authentic labor, why should I pretentiously reject its scent? The smell is a pungent ammoniacal tang of pigeon droppings and cow urine, the stench of lime and animal fat, and the slightly decayed sweetness of various plant dyes—saffron, mint, indigo—as they ferment. All of this blends together to form a powerful, undeniable field of life, one that reveals that the birth of beauty is never a fragrant, gentle affair.

Most of these dyers live in these squalid slums, but Fez's craftsmanship is perhaps primarily reflected in this unvarnished honesty. They confront every aspect of their labor, including its arduousness and unrefined elegance, and ultimately transform it into an integral part of beauty.

One cannot help but lament that we modern people are accustomed to selecting flawless industrial products in bright and clean shopping malls. We enjoy the results but isolate ourselves from the process.

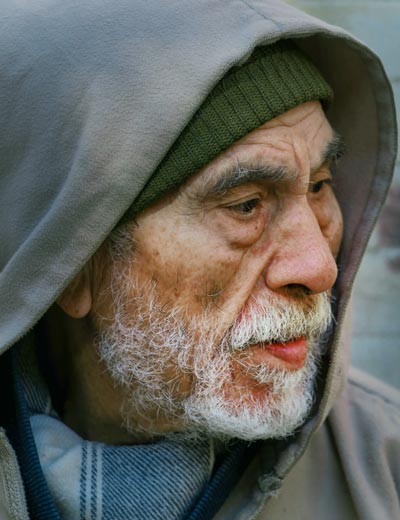

The sun's rays shone brightly on an Arab sage, who seemed to remind us not to forget that behind every smooth texture and every even color lies a rough yet sincere struggle of the flesh, filled with sweat, scent, and long waits.

In the mid-12th century, the continuous influx of immigrants from Central Africa, Spain, and even Turkey, including numerous artisans, merchants, and intellectuals, transformed Fez into the world's largest city and the most developed city in the Arab world for handicrafts, boasting over 100,000 houses and thousands of workshops. It was not only a religious and cultural center brimming with wisdom and art, but also a renowned center for handicraft production, known as the "Athens of Africa."

Fez's ceramics, mosaics, and bronze and silverware, blending Eastern and Western techniques, have earned it a place among the world's foremost craftsmen. Besides being renowned for its handcrafted leather, Fez's mosaic craftsmanship is also unparalleled today.

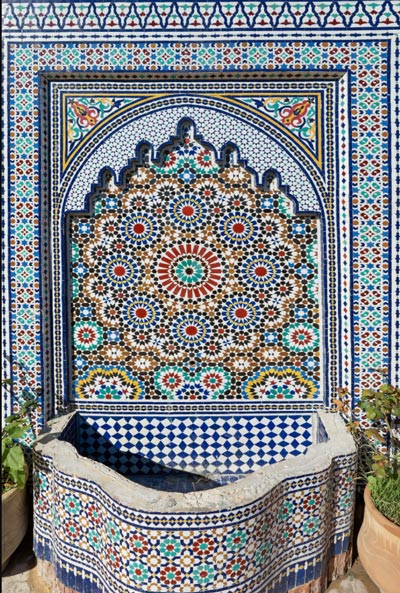

Morocco boasts world-class mosaic craftsmanship, and Fez's mosaics are a defining characteristic of the city. The mosaics of Fez not only inherit the ancient technique of firing a glazed surface, but also incorporate more intricate patterns and colorful Islamic elements. These vibrant and unique mosaics have become indispensable decorative murals in mosques, palaces, hotels, and living rooms.

Mosaic is one of the oldest known decorative arts, originating in ancient Greece in the Mediterranean. During the Byzantine Empire, mosaics reached their peak, becoming an indispensable mural decoration in churches and palaces. The mosaics of Fez not only inherit the ancient technique of firing a glazed surface, but also incorporate more intricate patterns and colorful Islamic elements, making them a leader in the industry.

Visiting the mosaic production center in northern Fez reveals a world of tranquility and intricacy, compared to the vibrant and intense atmosphere of the dyeing workshops.

The artisans here are undoubtedly the most outstanding ambassadors of the ancient city of Fez. Unfazed by their undivided attention, they revel in the inlaying and polishing of their work, hand-painting mosaics on exquisite porcelain, then filigreeing, hammering, gluing, and gluing...

It's said that the creation of a single work of art can take anywhere from a few days to months or even years. Even neighboring Algeria, which doesn't have diplomatic ties with Morocco, employed Fez mosaicists to guide the construction of its Great Mosque!

The old craftsman before me, his wrinkled and calloused hands, precisely placed every dot and line. He's not just crafting a decorative panel; he's like a contemplative philosopher, using color and form to perform a silent prayer, calculating the mysteries of the universe. Day after day, year after year, these skilled artisans in Fez, clumsily manipulating primitive tools, yet with masterful skill and awe-inspiring patience, they meticulously and meticulously create the world's most beautiful and dazzling mosaics. This series of images cannot fail to leave a deep impression on even the impetuous modern mind—this is the true spirit of craftsmanship.

Symmetrical stars, swirling vines, endless floral patterns—these patterns possess a hypnotic allure. Known as "zellij," they are the fruit of artistic wisdom. The Arab prohibition of idolatry, in turn, inspired artists to devote their talents to abstract geometric and botanical motifs. They believed that these infinite, ever-expanding patterns were a mathematical expression and praise of the cosmic order created by God.

What patience and dedication this requires! A mosaic pool measuring just a few square meters might take a skilled artisan months to complete. This wasn't the physical, explosive tenacity of the dyeing workshop, but a restrained, intellectual endurance. It wove the human spirit, thread by thread, into the impenetrable pattern. Standing there for so long, I felt dizzy, as if the entire space were spinning amidst those repetitive, shifting lines. This beauty was calm, rational, yet equally captivating.

This mosaic wall was a different world. All the colors were a unique blue-green hue, unique to Fez, known as "Fes blue." Unlike the deep indigo found in the dyeing workshop, this blue was brighter and more elegant, as if the brightest parts of the Moroccan sky and the emerald waters of the Mediterranean coast had been fused together, imbued into the mosaic tiles.

In the courtyard, piles of clay piled high, and rows of unfired clay sheets lay drying. Their unadorned forms, imbued with the earth's natural ochre, silently awaited their baptism by fire. Located on the edge of the Sahara, the world's largest desert, Morocco suffers from perennial drought and water shortages. Therefore, the people gather volcanic ash, rich in beneficial trace elements, and mix it with clay, then bake it to create conical-topped tagines. The use of volcanic mud ash in the tagine, Moroccan national tableware, further demonstrates the ingenuity of the ancient Moroccan people.

A potter resembling Charlie Chaplin works at a turntable. Between his mud-soaked hands, a seemingly lifeless mass of mud seems to come alive as the turntable rotates. It rises gracefully, unfolding into a perfect shape. The process is imbued with a mysterious, creative joy. His hands, like the hands of the Creator, guide the clay toward its destined form.

But the real magic happens during painting and firing. The painters employ an ancient technique called "glaze painting," applying a special pigment containing metal oxides to the clay. Curiously, before firing, the colors of these paintings were dull, completely betraying their future splendor.

Then, they were sent into the kiln, tempered by flames exceeding a thousand degrees Celsius. It was fire, this cruel yet creative key, that finally unlocked the prison of color, allowing it to awaken, bloom, and solidify into eternal beauty within the extreme heat.

If mosaic collage is a rational poem, then the pottery of Fez is the most emotional child born from the union of earth and fire.

Leaving the mosaic craft center, I looked back and saw the towering Minaret tower piercing the heavens. A flock of white doves soared to the sound of the bells, merging into the azure blue of North Africa.

I suddenly felt that the entire ancient city of Fez was like a vast, living kiln. Its labyrinthine streets are its passages, the bustling sounds and smells of its markets are its inner vitality, and the Mediterranean sun and the winds of the Atlas Mountains are its flames. For millennia, it has continuously forged life, faith, sweat, and time into the tangible, solid, and beautiful crystals of civilization before our eyes.

I climbed onto the terrace of a traditional house. From this vantage point, Fez revealed a different face: rolling hills beneath the Atlas Mountains, dotted with minarets, and the Merinid tombs stood silently in the sunset. I gradually understood that Fez's labyrinthine nature is not merely spatial, but also temporal and cultural.

The city itself is a vast artifact, shaped by decades of continuous construction, restoration, and transformation into the complex and organic whole it is today. Each generation leaves its mark on the city, while respecting the original structure and style.

This balance of continuity and change is the secret to Fez's ability to retain its ancient charm while remaining vibrant. Yet, it stubbornly reminds us: some value lies in slowness and repetition; some glory can only be achieved through lonely perseverance and physical toil.

The scent that permeates the city, the tinkling sound of hammers, are the living, rough yet warm breath of the ancient craftsman's spirit!